The 1987 March on Washington for Lesbian & Gay Rights wasn’t my first national march, not by a long shot. Barely a month into my freshman year of college, I participated in the first Vietnam Moratorium march on October 15, 1969, then exactly one month later, on November 15, I was a marshal at the huge New Mobilization1 (aka “New Mobe”) march. From my station between 6th and 7th Streets NW, I got to watch hundreds of thousands of people pouring down Pennsylvania Ave. ten or twelve abreast. I’d never seen anything like it.

I still have visceral memories of that one. It was sunny, but it was chilly and I was underdressed: In my innocence I thought my winter duds could wait till I went home for Thanksgiving. Wrong. I wasn’t the only one either. Those who’d worn jackets hadn’t brought gloves, so we took turns making coffee runs to the nearest drugstore then warmed our hands by wrapping them around the cup. Several of us entertained the others, and the police officers stationed on the same block, singing Tom Lehrer songs. I could go on . . .

So the 1987 March for Lesbian & Gay Rights wasn’t my first national march, but it was the first I’d had to travel to. I’d moved back to Massachusetts in the summer of ’85, and by now into my third year, it looked like I was going to stay there.

I’d marched in the the first national March for Lesbian & Gay Rights in 1979, of course, but I don’t remember who I marched with. Maybe the off our backs contingent, or the Washington Area Women’s Center? I do remember passing along the back side of the White House grounds chanting with a whole bunch of other dykes “Two, four, six, eight, how do you know that Amy’s straight?” Amy Carter, daughter of then-president Jimmy Carter, was all of 12 at the time. We were, of course, giving her the benefit of the doubt, but — I just looked her up — she’s been heterosexually married twice and has two kids, so straight she seems to be.

The AIDS Quilt, officially the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, was displayed for the first time during that march. Established almost exactly two years earlier, in November 1985, the Quilt at that point included 1,920 panels. Each panel was three by six feet; they were stitched into square blocks of eight panels each.

I knew about the Quilt. My friend Nancy Luedeman (1920–2010), a mainstay of Island Theatre Workshop and longtime partner of Mary Payne, had created a panel for four Vineyard men who had died of AIDS. I promised I would find her panel.

I was not prepared for how overwhelmed I felt as I walked down the rows between the blocks of panels. I’ve been deeply moved walking through cemeteries, noting the dates and the connections between people, but this was different: each panel was alive, evoking in color and imagery the life and personality of each person memorialized, each person lost. Finally I knew what it felt like to be in the presence of the sacred.

I did find Nancy’s panel. Two of the four men were identified by first name and last initial, the other two only by initials. This reflected the shame attached to AIDS, and homosexuality, on Martha’s Vineyard and in so many other places at the time. Nancy didn’t volunteer their full names, and I didn’t ask. I think Nancy said they’d all died off-island. Eventually I learned that Bill S. was Bill Spalding, who has another panel in the Quilt, with his full name on it. I don’t know about the others. If you do, please let me know.

The Quilt returned to D.C. a year later, and so did I. It had been on tour that spring and summer of 1988, growing all the while. By October 1988, spread out on the Ellipse, it comprised 8,288 panels. Too many to see all of them in only two or three hours, so I wandered, letting myself be drawn and directed by a name, an image, a thought.

A Red Cross caught my eye. I had worked at Red Cross national headquarters for four years in my D.C. days. That’s where I learned what an editor was, and where I started to become one. When I reached the panel and read the name on it, my knees collapsed under me. It was for my co-worker and friend Thom Higgins, whom I’d seen when I was in D.C. the previous October. He’d seemed fine. He didn’t say anything about being sick. He’d died earlier that year, I think in May.

My recollection is that Casselberry and Dupree were singing “Positive Vibration” at the other end of the Mall, but maybe I made that up. Now I can’t hear that song without thinking of Thom. I can’t think of Thom without hearing that song.

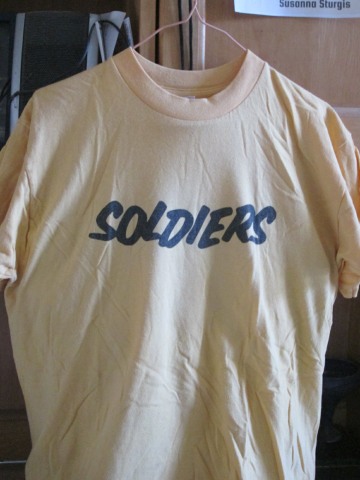

More about Thom in “1978: ERA March and the Red Cross Training Office.” He gave me my EDITOR shirt and my WHEN IN DOUBT TURN LEFT shirt. I still have both of them. I remember you, Thom.

NOTE

- Formally the New Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam. The successor to the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, which organized major antiwar events in 1967 and ’68, this was the coalition that organized the gigantic November 15, 1969, march. Frequently confused and/or conflated with it was the Vietnam Moratorium Committee, which organized the October 15 events across the country. It also organized the incredibly moving prelude to the November 15 march: On November 13 and 14, thousands of people walked from Arlington National Cemetery to the White House, each one bearing on a placard the name of someone killed in Vietnam. In front of the White House these placards were deposited into coffins set up for the purpose. I was involved in the housing and feeding operation ongoing at Georgetown and so was unable to participate. ↩︎