The July 9, 1978, march to extend the deadline for ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was the “largest march for women’s rights in the nation’s history” up to that time. Organizers, led by NOW (the National Organization for Women), were overwhelmed by the unexpectedly large turnout, and the march stepped off an hour and a half late. On short notice, owing to the huge crowd, the police had to close off all of Constitution Avenue, instead of just the anticipated half.

Of course I went. Everyone I knew went. For those of us in the D.C. area, rallies and demonstrations were easy to get to, and get to them we did. We’d often have out-of-towners crashing on our couches and floors. It wasn’t till the Second National March for Lesbian and Gay Rights on October 11, 1987, two years after I’d moved to Martha’s Vineyard, that I actually had to travel to a demo. (Yes, I have the T-shirt, and don’t worry, we’ll get to it eventually.) Massive demonstrations were old hat to me. I had to be reminded how life-changing they could be for first-timers — as indeed the November 1969 March on Washington to End the War had been for me.

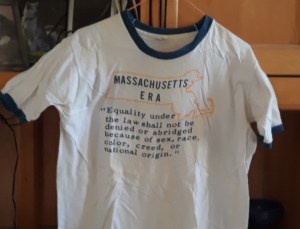

The colors of the women’s suffrage movement, gold, white, and violet (the initial letters of which, I’ve been told, signified “Give Women the Vote”), were much in evidence, on signs and banners as well as the T-shirt. Alice Paul, founder of the National Woman’s Party and a key organizer in the early 20th century suffrage movement, had died exactly one year before, on July 9, 1977. By bringing the militant tactics of the British suffrage movement to the U.S. she had helped revitalize and expand a flagging movement.

The British movement’s colo(u)rs were, by the way, purple, white, and green. For more about the suffragist colors, see this article. It doesn’t mention the “Give Women the Vote” connection, which may have well have been invented post facto by someone who preferred violet to purple.

After the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920, Alice Paul’s focus turned to securing legal equality for women through the ERA, which she drafted with Crystal Eastman (who was, among other things, a co-founder both of the Congressional Union, forerunner of the National Woman’s Party, and of the ACLU) and first introduced in Congress in 1923. It was widely known then as the Lucretia Mott Amendment, after the pioneering abolitionist and suffragist leader. The original ERA was rewritten in 1943 and has since been widely known as the Alice Paul Amendment. The text: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

It’s so unassuming, so self-evident and logical, that it’s hard to credit how revolutionary it remains. Forty-two years after that march, the ERA still hasn’t passed. For a brief history of the ERA, and where it stands now, here’s some background and some FAQs.

I didn’t get this T-shirt at the march, however. It was given to me by my boss at the time, Betty O., director of the Office of Personnel Training and Development (OPTD, aka “the training office”) at Red Cross national headquarters. That’s part of the story too.

As a job-hunting fledgling clerical, I’d been terrified by my glimpse of the typing pool at a big Boston insurance company. Oddly enough, my first permanent assignment at the Red Cross was in the Insurance Office. Here nine employees were crammed into a drab office, most of whose floor space was devoted to file cabinets. At one end the clerks spent most of the day following up on and filing insurance claims of all sorts: worker’s comp, unemployment, motor vehicle, medical, and so on. The other end was occupied by the three professional staff and the two secretaries, the junior of whom was me. I worked for the assistant director, a nice guy who wasn’t all that bright, and the insurance specialist, a woman who was very bright and not nice at all, quite possibly because her two superiors were nowhere near as competent as she was.

The big challenge of this job was boredom. I generally finished my typing and filing in barely half the time allotted, which gave me plenty of time to do Women’s Center work. Like most bright kids, in school I’d developed a facility for what wasn’t yet called multi-tasking: I could do math homework in English class and still have the right answer when the English teacher called on me unexpectedly. Gradually this skill carried over into my non-work life, and not in a good way, like I’d be drafting a book review in my head while in a Women’s Center collective meeting and devoting full attention to neither one.

Gossip among Red Cross clericals had it that the Office of Personnel Training and Development was a good place to work, so when an opening for staff assistant (a clerical position one step up from secretary) appeared on the internal help wanted list, I applied and was hired. I had only a vague idea of what they did there, but this was a good move. Elizabeth Olson, known to all as Betty O., the training director, was one of the most remarkable people I’ve ever met. Born in 1914, she’d joined the Red Cross in 1943 and risen through the ranks, a woman who remained committed to her work and her career even as the postwar tide was herding women of her class and color into the home.

The training office developed and implemented internal training courses for a nationwide organization with four regional offices and myriad chapters, some large and others very small. These ranged from time management to effective supervision to training staffers to teach the various courses. It turned out to be interesting stuff. I had a long-running argument with one of the two assistant directors about the term “human resources,” which was replacing “personnel” in the business world at that time.[1] He embraced it; I hated it, maintaining that it reduced people to the status of widgets.

We were a small staff: director, two assistant directors, two staff assistants, and one secretary. At this time, many educated women were concealing their ability to type in the belief, often well founded, that if they let superiors and colleagues know they could type, they would wind up doing nothing else. Betty O. could type, but she didn’t conceal that fact because she realized that if she did some of her own clerical work, the clerical staff would be free to take on more non-clerical tasks and contribute to the mission of the office. And we did.

Thom Higgins quickly became my best Red Cross buddy. He was the senior staff assistant, a Vietnam vet a few years older than I. We quickly established that he was gay and I was a lesbian. Personal experience was already teaching me that gay men and lesbians were not natural allies: many of the gay men I ran into were unwilling to consider the possibility that they were sexist as hell, which they were. Thom wasn’t, something he attributed to the fact that he had six sisters and no brothers.

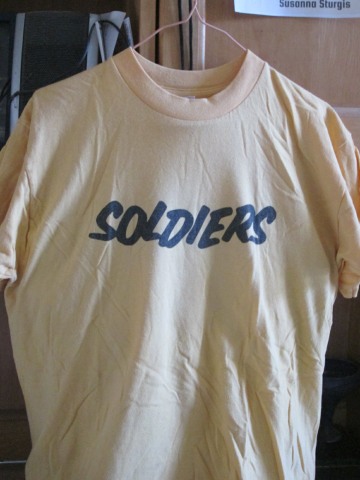

We became the core of a free-floating group that met at the rooftop lounge of the Hotel Washington[2] most Fridays after work to “process the week.” The group included Bruce Bant, an ex of Thom’s with whom he was still close friends, and Charles H., Thom’s current, who was an aide of some sort to some Republican congressman and who could have stepped out of an ad in GQ. Bruce, like Thom, was a Vietnam vet — they’d met in Vietnam, if I remember correctly — but unlike Thom he was career military. He’d recently retired as a sergeant major, having edited Soldiers, the enlisted service members’ magazine, and was now involved in the beginnings of what became USA Today.

I was the radical lesbian anti-militarist feminist in the group. We razzed each other endlessly about politics and the military but were always friendly about it. Although we were in Washington, the belly of the political beast, politics seemed a long way off. One Friday afternoon Bruce produced a Soldiers T-shirt and said he’d give it to me only if I promised to wear it. I promised, and I did, more than once.

Ever since starting the T-Shirt Chronicles, my favorite procrastination research technique has been looking up people, places, and events that my story touches on in some way. Thom died of AIDS in 1988 — I’ve got a story about that, and he comes up again before I learn of his passing — but I had no idea whether Bruce was still on the planet or not. A quick Google search found a LinkedIn entry that had to be him. He was living in Florida. Should I contact him? He probably had no recollection of me, but he might be able to place me if I mentioned the Soldiers T-shirt, the rooftop lounge at the Hotel Washington, and Thom.

Just now I went looking again. His LinkedIn page is still up, as is a Facebook timeline with an entry from February 2020, but near the top of the Google hits was the news that Bruce died in Fort Lauderdale on September 27, 2020. Also among the top hits was a guest column from the March 21, 2010, South Florida Gay News, entitled “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Has Been a Complete Failure.” The byline is Bruce Bant, Retired Army Sergeant Major. It’s him for absolute sure. I’m sorry I missed you, Bruce.

Notes

[1] The term itself dated back at least to the early 20th century, but it does seem that it was a hot topic in the 1970s. My tenure in the training office was 1978–79, so it seems plausible that it was a contested term at ARC NHQ at that time.

[2] Now, as far as I can tell, the W Washington, on 15th Street N.W. near Pennsylvania Ave.

If you don’t see a Leave a Reply box, click on the title of this post and scroll down.