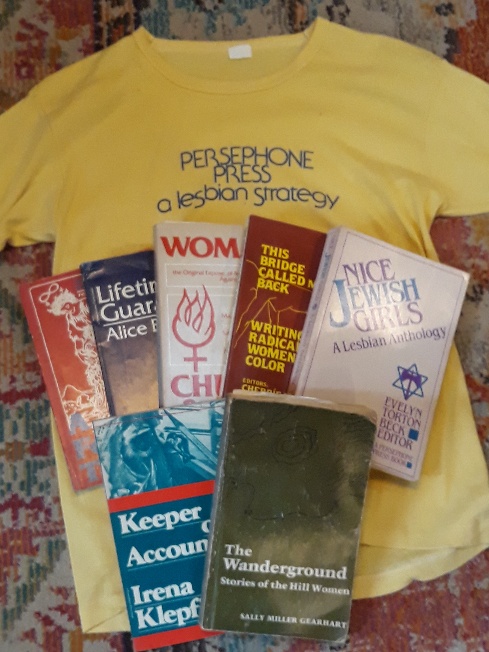

Persephone Press died in May 1983. Social media was decades in the future, but word spread through the feminist print network almost that fast. I still remember standing stock-still when I heard the news, unable to take it in. I was at Lammas, surrounded by the Persephone books that I sold every day, crucial, path-breaking books in the feminist and lesbian world. Lesbian Fiction, Lesbian Poetry, Nice Jewish Girls, This Bridge Called My Back, The Coming Out Stories, The Wanderground . . . Gone? Just like that?

Well, no, not quite. By then I was well aware of the economic tightrope that a small, undercapitalized bookstore had to walk day in, day out, to keep books on the shelves. I had some idea of the similar constraints that publishers operated under, but somehow I’d assumed that Persephone was exempt. No matter how well you know the technical details, magical thinking has a way of working its way into mind and heart when you need to believe.[1]

I couldn’t imagine a world in which Persephone didn’t exist, but the unimaginable had happened. Persephone was gone.

Persephone Press was brilliant. It didn’t invent the anthology format, but it recognized how perfectly suited it was to feminist publishing at that particular time. So many women were moved — inspired, compelled, driven — to write because so little of what was out there reflected our lives or answered our questions. We wrote what we wanted and needed to read.

But most of us had to work our writing time in around our jobs, our political and other volunteer activities, and our family responsibilities. Sometimes we were learning our craft almost from scratch, which meant struggling to overcome everything we’d learned along the way about what good writing was and who was entitled to write. It helped to find sisters on the same journey so we could assure each other that we weren’t crazy, we could do it, and what we had to say was important.

Novels and other book-length works can be written under such conditions, but shorter ones are easier not only to finish but to get out into the world in print and/or in performance. Not surprisingly, the most accomplished writing emerging from the grassroots feminist movement from the late 1960s into the ’80s consisted of poetry, short stories and essays, and novels, more or less in that order.

Unfortunately, that was pretty much the opposite of what most readers wanted to buy, and bookstores specialized in, well, books. We carried newspapers and journals, of course, and they published short-form writing of all sorts, but they also had a short shelf life. Anthologies combined the best of both forms. They brought together important new, recent, and sometimes not-so-recent writing that was otherwise scattered across time and multiple journals of limited circulation. They could combine poems, stories, and essays between the same two covers. They took longer to produce, but they stuck around a lot longer. In addition, the works collected into a well-edited anthology communicate with each other simply because they’re in the same place at the same time. The whole, in other words, is even greater than the sum of its parts.[2]

Persephone’s anthologies had no precedents. At the time, most of their contributors were known, if they had published at all, only in limited circles, but many of them went on to become widely known and read far beyond the feminist print world. After the crash, most Persephone titles were picked up by other publishers and remained in print for years if not decades. The fourth edition of This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color — “a work which by the mere fact of its existence changed the face of feminism in the United States”[3] — was brought out in 2015 by SUNY Press.

Now I look at the numbers — four titles published in 1980, and four in 1981 — and wonder What were they thinking? Most of these were physically big books. Several were going to take a while to reach their audience, like the reprint of Matilda Joslyn Gage’s amazing Woman, Church & State (1893). Anything with “lesbian” in the title and the lesbian romance Choices were going to sell well in the feminist, lesbian, and gay worlds, but those worlds were were not large.

Not to mention — for an undercapitalized publishing company “selling well” could turn into a curse. Invoices were supposed to be paid in 30 days, but undercapitalized bookstores were often doing well to pay in 60. The printing bills, in other words, were going to come due long before they could be paid out of cash flow.

And they did.

What were they thinking?

The recriminations that followed Persephone’s demise were so widespread and so bitter that Persephone’s existence seems to have been erased except for those who know where to look. I wasn’t privy to any of the dealings between press and authors, and I’m not going to repeat what I heard second, third, and fourth hand, but a short article that appeared in the November 1983 off our backs provides some insight. Three significant points:

- “Because their books were selling well, they were constantly back on the press. This tied up $40,000 to $50,000 in printing and production costs, which added to the cost of overhead, and bringing out new titles was more than Persephone could handle.”

- Cofounders Pat McGloin and Gloria Greenfield “[decided] to consistently operate their press according to feminist ideals. They paid royalties to their authors twice the standard paid by the publishing industry, and refused to allocate a lion’s share of their promotions budget to one best seller and and distribute what was left to the other books.”

- Greenfield and McGloin expressed disappointment with the lack of support from the feminist community.[4]

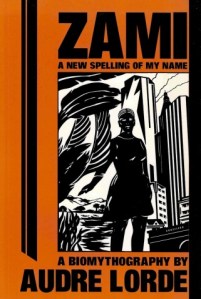

Short version: Persephone’s business plan played fast and loose with real-world economic realities, and the “feminist community” didn’t step up to close the gap. In addition, the scheduled books that never got published, like Barbara Smith’s Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology, and the published books that didn’t get adequately supported, like Audre Lorde’s Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, were by women of color, whose publishing options at the time were the most limited.[5]

Plenty of anger was directed at Pat and Gloria, and Pat and Gloria seem to have directed at least some of theirs at “the feminist community,” but I suspect that deep down much of rage and frustration was directed at the economic system that thwarted our needs and our expectations as women, as feminists, as lesbians. Persephone’s 15-book list made it so clear what we were capable of, had given us so much to hope for, and capitalist economics, coupled with lack of organizational and individual support, had cut us off at the knees.[6]

Gazing now at my Persephone Press T-shirt, I’m tempted to take “A Lesbian Strategy” as a cruel, unintentional joke. Had our strategy, if that’s what it was, come to a dead end? Then I remember all the writers and works that Persephone encouraged, and the effects they’ve had on the world we live in now. Most of those whose lives have been enriched by Persephone’s legacy probably don’t know her name, and for those who do the legacy is tinged with understandable bitterness and regret.

After Persephone died, I tried to write a eulogy. It was a poem, three or four pages long; I wasn’t satisfied with it, and I’ve long since lost track of the whole thing, but I liked part of it so much I put it on a postcard:

She comes back indeed.

notes

[1] The dangers of magical thinking carried to extremes were laid out brilliantly by James Tiptree Jr. (Alice Sheldon) in her 1976 story “Your Faces, O My Sisters! Your Faces Filled of Light!” Its protagonist believes she’s living in a city where misogyny doesn’t exist and it’s safe to be on the road at night. Spoiler alert: it’s not.

[2] Here are some of the anthologies on my shelves that were published in the 1980s, almost all by feminist presses. To keep it relatively brief, I haven’t included strictly fiction anthos.

- For Lesbians Only: A Separatist Anthology, ed. Sarah Lucia Hoagland and Julia Penelope, Onlywomen Press, 1988

- Out from Under: Sober Dykes & Our Friends, ed. Jean Swallow, Spinsters, Ink, 1983

- Sex Work: Writings by Women in the Sex Industry, ed. Frédérique Delacoste and Priscilla Alexander, Cleis Press, 1987

- Shadow on a Tightrope: Writings by Women on Fat Oppression, ed. Lisa Schoenfielder and Barb Wieser, Aunt Lute Books, 1983

- That’s What She Said: Contemporary Poetry and Fiction by Native American Women, ed. Rayna Green, Indiana University Press, 1984

- The Tribe of Dina: A Jewish Women’s Anthology, ed. Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz and Irena Klepfisz, Sinister Wisdom 29/30, 1986

- With the Power of Each Breath: A Disabled Women’s Anthology, ed. Susan E. Browne, Debra Connors, and Nanci Stern, Cleis Press, 1985

- Women-Identifed Women, ed. Trudy Darty and Sandee Potter, Mayfield, 1984.

[3] Feminist Collections, vol. 5, no. 1 (fall 1983). This is one of the best contemporary Persephone post-mortems I’ve found yet. Feminist Collections was an indispensable quarterly review of women’s studies resources out of the University of Wisconsin, then edited by Susan Searing and Catherine Loeb. In 2018 it morphed into Resources for Gender and Women’s Studies: A Feminist Review.

[4] Mary Kay Lefevour, “Persephone Press Folds,” off our backs (November 1983), p. 17.

[5] I read Zami as soon as it came out, but my original copy went wandering. I almost certainly brought it with me to Martha’s Vineyard, but probably I lent it to someone and — well, it went wandering. The copy I have now was reprinted by Crossing Press after it was acquired by Ten Speed Press in 2002. The cover is new, but “Text design by Pat McGloin” on the copyright page clearly indicates that the text itself is from the first edition. There’s no indication anywhere that Audre Lorde died in 1992. At least one edition has appeared since with a different cover, but it too seems to use the text from the first edition. I just found this excellent 2014 assessment of Audre Lorde’s importance — and who kept her words alive till the wider world was ready to “discover” her. The author is Nancy K. Bereano, editor of Crossing Press’s Feminist Series until she left to found Firebrand Books. Several publishers continued the work of Persephone Press, but if I had to single out two of them, they’d be Firebrand and Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press.

[6] See note 1.

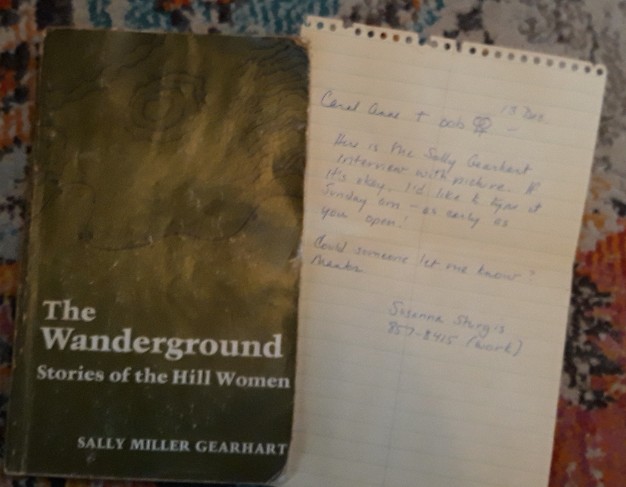

This note was tucked into my well-worn copy of The Wanderground. Dated 13 Dec. [1979], it’s addressed to Carol Anne [Douglas] and off our backs women: “Here is the Sally Gearhart interview with photo. If it’s okay, I’d like to type it Sunday a.m. – as early as you open! Could someone let me know? Thanks.” My interview with Sally appears in the January 1980 off our backs.