WisCon, the world’s first and probably only fantasy/science fiction convention that focuses on feminist speculative fiction, was born in 1977 in Madison, Wisconsin. Thanks to Joan Nestle at the Lesbian Herstory Archives, an avid f/sf fan, I learned about it and f/sf fandom, including feminist f/sf fandom, before too many years had passed; see “I Discover Women Writing F/SF” for details.

But it wasn’t till February 1990 that I attended my first WisCon, WisCon 14. I got there by a circuitous route, which looks something like this:

In the late 1970s, having got wind of the wealth of fantasy and science fiction being written by women, I started haunting Moonstone Bookcellar, the f/sf bookstore on Connecticut Ave., near Washington Circle. After a skim through the pages, I’d buy almost anything with a woman’s name on the cover.

While several of us were prepping for my 30th birthday party, in June 1981, Mary Farmer, owner and manager of Lammas, D.C.’s feminist bookstore, asked me to sign on as Lammas’s book buyer. Once I got my bearings, surprise, surprise, I started building up the store’s f/sf collection.

In 1984, Carol Seajay, founder, editor, and publisher of Feminist Bookstore News, invited me to become FBN’s first columnist. “Susanna Sturgis on Science Fiction” debuted shortly thereafter. Big perk was that I could now get free review copies from publishers.1

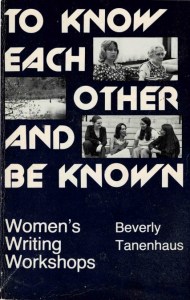

Also in 1984, I attended the Feminist Women’s Writing Workshops for the first time. FW3 in those years was held at Wells College in tiny Aurora, N.Y., but was based in Ithaca, 30 miles away. I got to meet Irene “Zee” Zahava, proprietor of Smedley’s, Ithaca’s feminist bookstore, and Nancy Bereano, then the editor of Crossing Press’s great feminist series and about to establish her own trail-blazing Firebrand Books.

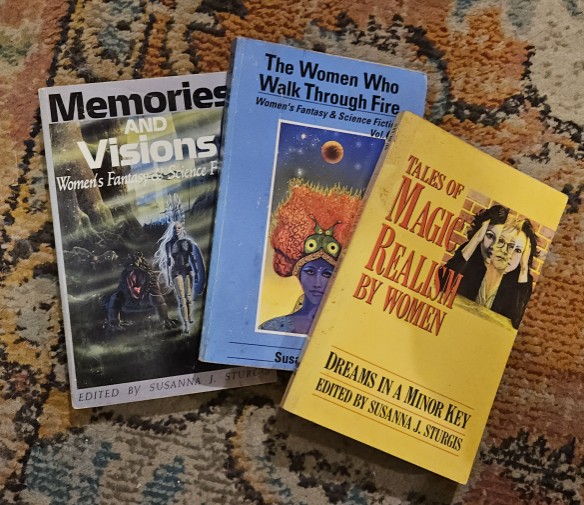

Zee was just starting to edit anthologies, often of women’s writing; by now she has edited a gazillion and branched out into offering writers’ workshops. Back then, however, she opened the way for me to edit three anthologies of women’s f/sf for Crossing: Memories and Visions (1989), The Women Who Walk Through Fire (1990), and Tales of Magic Realism by Women (Dreams in a Minor Key) (1991).

By the time Tales of Magic Realism came out, my relationship with Crossing had frayed so that was my last anthology. Personalities aside, the real underlying problem was the structural disconnect between feminist publishing and feminist f/sf readers. Feminist publishing and bookselling emphasized the trade paperback format; f/sf was overwhelmingly a mass-market world. Feminist f/sf fans could find their favorite women authors in f/sf bookstores. Only a handful of feminist booksellers knew f/sf well enough to build a feminist f/sf section, notably Karen Axness at Room of One’s Own in Madison and Paula Wallace at Full Circle in Albuquerque.

While at Lammas I had stocked a fine feminist f/sf section, which f/sf fans appreciated but was a hard sell to other fans of fiction by women. The widespread conviction that f/sf was only about spaceships and elves resisted all my attempts to unseat it.2 But my work at Lammas and especially my Feminist Bookstore News column did catch the attention of Crossing Press and others.

Among those who noticed my FBN column was the archivist/librarian for the Boston chapter of Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), who was also the East Coast half of fantasy writer J. F. Rivkin. In those days female protagonists had become more common in f/sf, but often they were the only woman in a team of men. If a novel had two significant female characters, they tended to be rivals, not allies. So J. F. Rivkin’s first novel, Silverglass (1986), was right up my alley: sword & sorcery featuring lesbian partners who had adventures together.

J. F. Rivkin/East was also well connected with the women writers in the New England f/sf scene, which is how I came to be included in a group signing at Glad Day, Boston’s gay bookstore, then located on Boylston Street near Copley Square. I’m pretty sure the year was 1990, after The Women Who Walk Through Fire came out that spring and after I had attended my first WisCon in February. There for the first time I met Ellen Kushner, Delia Sherman, Melissa Scott, Lisa A. Barnett, and “J.F./East” herself. Wow.

With WisCon and that momentous Glad Day signing, a whole world opened up, one I’d been only dimly aware of in my feminist bookselling days. Not only did it keep me busy for most of the 1990s, it greatly expanded my T-shirt collection, thanks in particular to the wonderful Ts created by Freddie Baer for the James Tiptree Jr. Award. The Tiptree, for speculative fiction that explores and expands our understanding of gender, was launched by authors Pat Murphy and Karen Joy Fowler at WisCon 15, my second WisCon, and I chaired the Tiptree jury in 1994. More about that later.

NOTES

- I continued writing the f/sf column till 1996, 11 years after I left D.C., so the freebies continued to arrive. Since I was only interested in the ones by women, I’d take the rest down to Book Den East, which sold used and rare books, and sell them. Bookseller Cindy Meisner [1944–2023] told me these were snatched up by young male sf fans who loved getting brand-new books for cheap. ↩︎

- Genre fiction per se was never the problem. Mysteries have been huge in the feminist press since they were introduced, and don’t get me started about lesbian romance. Lammas customers would tell me they found fantasy or science fiction too unbelievable then come to the check-out counter with a lesbian romance about a nice lesbian on vacation who falls in love with a slightly older woman who turns out to be independently wealthy and they live happily ever after. ↩︎