Where to begin? The family I grew up in had upper-crusty antecedents on both sides — New England on my father’s side, Virginia/Maryland/New England on my mother’s — but we looked middle/upper-middle class. My father was an architect. My mother didn’t work outside the home while my brothers, sister, and I were growing up. She talked with such evident longing about having done summer stock theater after WWII (during which she was in the SPARs, the women’s unit of the Coast Guard Reserve) that when I first read Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night my senior year of high school, I connected her instantly with Mary Tyrone, who clings to a belief that she could have been a concert pianist if only she hadn’t got married.

That was not the only connection between my mother and Mary Tyrone: the latter was addicted to morphine, while my mother’s drug of choice was alcohol. She didn’t stop drinking till after a family intervention when I was in my mid-40s. As a teenager I was deep down convinced that if I drank, I would become an alcoholic too. So I didn’t drink.

In my mid-teens, however, I started eating compulsively. Between the beginning and end of junior year I gained 40 pounds and was totally oblivious till spring weigh-in in gym class. It took several years before I intuited the connection. Nancy Friday’s book My Mother, My Self came out in 1977, the same year I did, in case I needed any encouragement.

Alcoholism was no secret in lesbian and gay communities. For many years, lesbian and gay life had revolved around bars, but even in the late ’70s, when we were conscientiously creating “chem-free” spaces and events, it was impossible to avoid. By the early ’80s we were arguing about ways to deal with it. In the feminist and lesbian circles I moved in by then, the 12-Step program of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Al-Anon was suspect from the get-go for its heavily patriarchal Christian God orientation. I didn’t know how to go about finding meetings that welcomed gay men, lesbians, and/or feminists. Coming up with effective alternatives, however, was a challenge.[1]

Among the first things I did when I landed on Martha’s Vineyard was go looking for a 12-Step program. They weren’t hard to find: both weekly papers included lists of meetings for several programs, mainly AA, Al-Anon, Narcotics Anonymous (NA), and Overeaters Anonymous (OA). That first fall I attended a couple of Al-Anon meetings. Most of the attendees were women with alcoholic husbands or ex-husbands. I was a lesbian who had grown up with an alcoholic mother but had left home a long time ago. They were dealing with day-in-day-out reality; I was dealing with patterns rooted in the past.

Since food was obviously my drug of choice, I tried a couple of OA meetings. At the time the few OA options on the Vineyard followed the “Grey Sheet” plan, which looked like, and indeed was, a diet. Not what I was looking for. I wanted to deal with the compulsion part, not control the calories I was taking in.

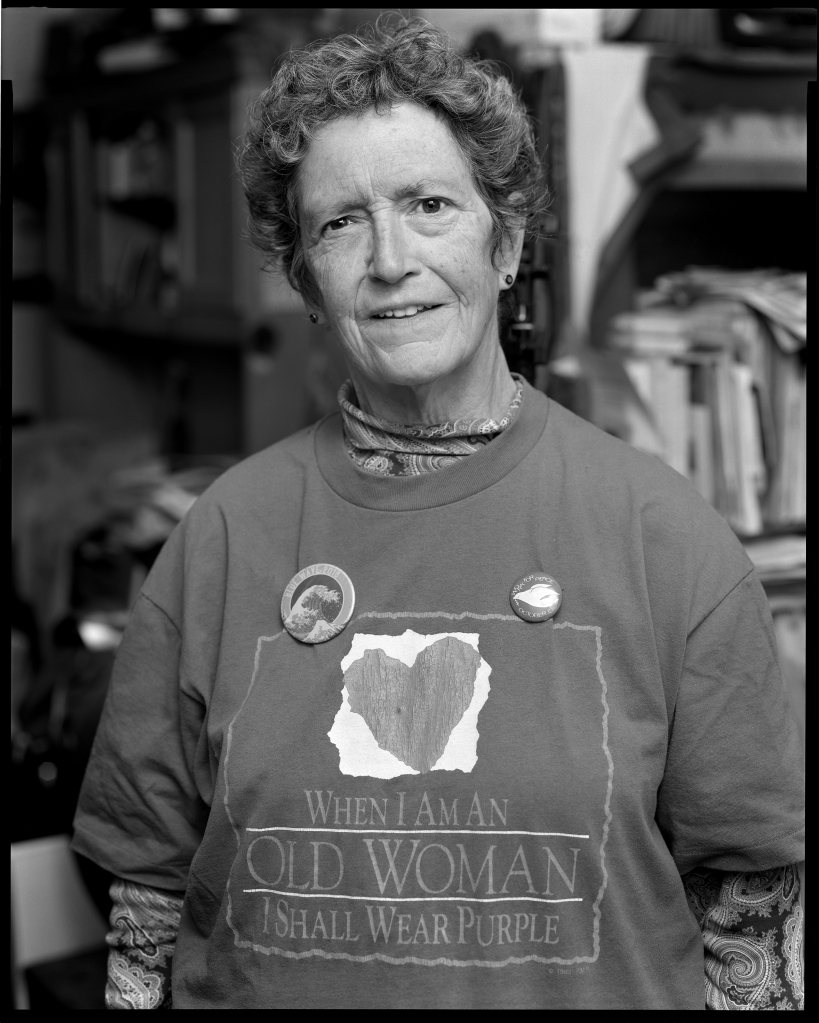

Then I found an Adult Children of Alcoholics (ACA) 12-Step meeting in the doctors’ wing of Martha’s Vineyard Hospital. There I found my tribe. I kept coming back. I was asked to lead the fourth meeting I ever attended. I didn’t realize at the time that this was highly unusual. Leading the meeting was Mary Payne, who was sure not only that the newcomer was, like her, a lesbian but that she would come out if she had to introduce herself. She had my number: I was and I did. On the Vineyard in the mid to late ’80s, gay men and lesbians lived mostly under the public radar. We knew each other, but no one was, as they say, “flaunting it.” This was my invitation. A door opened up. I walked through it, not knowing what the reaction would be. The reaction in that ACA meeting was pretty much “No big deal” and “Keep coming back.”

Along with being the chair of that particular meeting, Mary (1932–1996), the founding director of Island Theatre Workshop (ITW), was frequently described as “a dynamo.” This is 100% accurate. She was under five feet tall but had the presence and impact of a six-footer. AA’s 11th Tradition says that “our public relations policy is based on attraction rather than promotion.” Mary’s PR policy was the exact opposite: she was a tireless promoter, and in her worldview the overlap between theater and recovery was significant. Come by the theater — Katharine Cornell Theatre, “KC” as I soon learned to call it — during a rehearsal, said Mary. ITW was rehearsing Molière’s The Miser. I could help with PR. (This was probably my introduction to the Tisbury Printer, which printed all of ITW’s posters and programs.)

I hadn’t done theater since high school, but over the years I’d often been at least on the peripheries of the performing arts, especially music. Hallowmas, my D.C. writers’ group, had given public readings. I was tempted, but I was also terrified. I envisioned the theater as a cavernous space with tiny figures at the far end, none of whom I recognized and none of whom noticed me.

When I finally mustered the nerve to walk up the outside stairs and open the door for real, what I saw was a cozy, even intimate space, flooded with light from tall multi-paned windows on both sides. Between the windows were four giant murals, two on each wall, depicting scenes from island history and island life.[2] In the mid-1980s the seats were covered in a green vinyl that could emit a sound like flatulence if you changed position. They’ve long since been replaced by a textured blue fabric that remains blessedly silent.

The front of the house, just in front of the proscenium stage, was bustling with activity. Rehearsals usually had two or three dogs in attendance: Mary’s Schipperke, Jenny; Nancy Luedeman’s Lhasa Apso, Featherbell; and Lee Fierro’s Meggie, who was larger than the other two but not by much. Dogs were of course verboten in KC, and equally of course Mary and company ignored the prohibition.

I was quickly hooked. Mary was impossible to say no to, but the reasons for “yes” were compelling. I was still getting my bearings on the Vineyard, still half thinking that I was just here for a year, and here, abracadabra, was a ready-made multigenerational circle of interesting friends and acquaintances, quite a few of whom were lesbian or gay. I got included in potlucks, holiday gatherings, and birthday parties. I got part-time jobs and house-sitting gigs through theater connections. On solstices, equinoxes, and cross-quarter days — the sacred days between the solstices and equinoxes: Samhain (Hallowmas), Brigid (Candlemas), Beltane (May Eve), and Lammas — Mary often hosted witchy celebrations in her living room.

Not surprisingly, all this theatrical ferment affected my writing. I set aside the novel I thought I’d come to the Vineyard to write. What came out of my pen and my brand-new computer was poetry, along with reviews and occasional essays for the lesbian and feminist publications I hadn’t quite left behind. My two first stage-managing gigs, first of Shakespeare’s Scottish Play and then of Medea, inspired work that I’m still proud of, including “The Assistant Stage Manager Addresses Her Broom After a Performance of Macbeth” (see below). I was giving readings and sometimes hosting an open-mic poetry night at Wintertide Coffeehouse (you’ll hear more about Wintertide in a future post). “MacPoem,” as I came to call it, was my favorite performance piece.

Step 2 of the 12-Step Program: “Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.” Theater was part of that power for me. While growing up, I had associated theater with addiction, so it was wildly appropriate that it become part of my recovery. Mary’s approach was, to say the least, unorthodox, but it worked.

Notes

[1] This was what prompted me in the early 1990s to write a series of columns for the feminist wiccan journal Of a Like Mind, on working the steps from a pagan/feminist perspective. In keeping with the 11th and 12th Traditions, these were bylined “A Pagan Twelve-Stepper.” They were popular enough to be collected into a pamphlet, which I’ve still got a copy of.

[2] Before long I learned they’d been painted by Stan Murphy (1922–2003), the eminent Vineyard artist.

* * * * *

the assistant stage manager addresses her broom after a performance of “macbeth”

Who am I? Let me tell you what I do.

Within these walls I manage time and space,

make sure the pitcher’s on its hook before

its bearer wants it, warn the messenger

he’s on soon, check to see his torch is lit

and that the backstage lights are out. Right now

I’m cleaning up debris from this night’s show.

Is this a dagger I see before me?

It is, but split in pieces. I’m the one

who tapes it back together after hours.

Tomorrow night this plastic dagger turns

to steel, honed sharp enough to pierce a haunch

of gristly meat — or Duncan’s royal breast.

Before each show I sweep the stage. I see

green needles strewn where Birnam Wood has come

to rest the night before. I shiver, chilled,

as if I’d slept and woken centuries hence

with all my friends and family dead. And then

I sweep them all away. “Out, out, damn trees!”

I cry, “You haven’t come here yet! Begone!”

Here, separate ages stream like shimmering strands

in one great waterfall, and time dissolves.

Mere mortals we, what havoc do we wreak?

Elizabethan Shakespeare conjured up

Macbeth, medieval Scottish thane, and we

invoke them both, in nineteen eighty-six.

I watch the people enter, choose their seats,

and rustle through their programs. Normal folk,

it seems, and yet this gentle summer night

they’ve purchased tickets to a barren heath,

a draughty castle primed for treachery.

Right now the lights are up, the theatre walls

are strong, the windows fixed within their frames.

At eight o’clock the howling winds begin,

the wolves close in, the sturdy walls are gone.

These common folk, I wonder, have they bought

enough insurance? Have they changed their bills

for gold and silver coin? If challenged by

a kilted swordsman, how would they explain

their strangely tailored clothes?

No loyal lord

or rebel threatens me. Between the worlds,

or through this velvet curtain, I can move

at will. I warn the sound technician, “Ten

more minutes,” then I pass backstage to say,

“The house is filling up.” The Scottish king

is drinking ginger ale; a prince-to-be

in chino slacks is looking for his plaid.

The Thane of Glamis is pacing back and forth,

preoccupied with schemes to win the crown,

or trouble with his car. I prowl backstage,

alert for things and people out of place.

Last night I found a missing messenger

outside the theatre, smoking cigarettes.

I called him back in time: Macbeth’s bold wife

demanded news — What is your tidings?; he

was there to gasp, The king comes here tonight!

No phone lines run to Inverness, no news

at six o’clock. (Walter MacCronkite’s face

appears and says that base Macdonwald’s head

was nailed upon the wall, that Cawdor’s fled

and Glamis has been promoted; polls predict

he might go higher still.) The kingdom’s nerves

are messengers who run from king to thane

to lady. Take the Thane of Ross, who comes

to tell his cousin that her husband’s flown

to England, leaving her unguarded; then

he takes himself abroad, to where Macduff

and other rebel lords are planning war.

Macduff’s unguarded lady fares less well.

A breathless runner pleads, “Be not found here;

hence, with your little ones!” but on his heels

come murderers, death-arrows from the king.

Two sons, a daughter, and their mother die

with piercing shrieks that vibrate in my spine.

With piercing shrieks vibrating in my spine,

I contemplate a different line of work;

this sending harmless people to their deaths

is bad for my digestion, and what’s more,

it’s happening much too often. First I let

King Duncan in, and he gets killed in bed.

Could I have known so soon that Cawdor’s heart

was rotten? No. But shortly after, I

send scoundrels to the banquet hall; Macbeth

himself has called them. Not the kind of guest

that Duncan entertained! And then I tell

Macbeth’s friend Banquo and his son it’s time

to join the party. What about the thieves

I know are lurking on the gate road, dressed

to kill? But Banquo is a fighting man,

well-armed, and Fleance does escape. Not so

Macduff’s fair lady, and her kids. Could I

prevent their deaths? What if I plied the brutes

with Scotch? They might get drunk enough to lose

their maps, or drop their knives, or fall asleep.

What if I whispered in the lady’s ear,

“Don’t go outside today — and bar the doors.”

I doubt she’d pay attention. Each one goes

to meet the dagger destined for his breast.

Perhaps I’d get my point across if I

could speak in rhyme and paradox, the way

the witches do, with fair is foul, and foul

is fair. The witches manage time and space

like me; you could call me the unseen witch.

I wonder, are they working from a script?

You’ll see: the second sister sweeps the stage

as I do, clearing them the space they need

to cast their circles. We both summon kings

and apparitions out of time, although

our methods differ some. “You enter soon,”

I warn, “stage right.” Mundane, compared to how

my sisters work, with Double, double, toil

and trouble, cauldron, fire, and lengthy list

of weird ingredients — the eye of newt

and toe of frog, the blood of sow that ate

her piglets — but we get the same results.

Our audience is moved to awe, and then

proceeds along its merry way to rendez-vous

with fate, or Birnam Wood, or man not born

of woman. They get blamed for it. I don’t.

The witches disappear, and one last time

prince Malcolm calls his kin to see him crowned

at Scone. The set is struck, costumes returned

to cardboard boxes, wooden banquet bowls

and Scottish flag to rightful owners; kings

go home to mow the lawn or fix the car.

Where did the blasted heath go off to? I

am leaning on my broom again. What stays

when all the parts spin off? Just memories

of daggers, prophecies, and anguished screams?

The air still tingles here. The gates remain

but smaller, well concealed. I might reach in

and conjure back that knife, that messenger.

“There’s knocking at the gate,” the lady says,

“Give me your hand! What’s done cannot be undone.”

To bed, she says. To bed, to bed, to bed.