Georgetown University is a Jesuit-run Catholic institution, and when I was there, 1969–1971, Catholic undergraduates were required to take four semesters of theology. Non-Catholics could take theology, but I opted for the alternative requirement, a two-year, four-semester course called Comparative Civilizations, aka “Comp Civ.” This was taught by Father Sebes, a diminutive older Jesuit whose academic background was in Far Eastern studies. The course covered Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, and Taoism, and might (can’t remember for sure) have included some mention of the various flavors of Christianity. We referred to it as Pagan I and Pagan II.[1]

What was my image of “pagan” at that point? Surely I associated “pagan” with the gods and goddesses of ancient Greece and Rome, with the likes of Socrates, Plato, and Julius Caesar. The myths were interesting, but they were “back then,” history, and ancient history at that. Besides, the Christians had vanquished the pagans, right?

That changed big-time when I moved back to D.C. in 1977 and came out into lesbian and feminist communities that had been discussing religion, spirituality, ancient history, and related issues for years, and not with academic detachment either. Paganism, loosely defined or not defined at all, was alive, lively, and everywhere. Interest in Wicca, especially of the women-only Dianic sort, had been growing and deepening for at least a decade. (Diana and her Greek counterpart, Artemis, being the very rare goddesses who had as little to do with men as possible.)

Take Lammas Bookstore, where I quickly became a regular customer and eventually, in 1981, the book buyer. Founded in 1973, Lammas was named for the cross-quarter day between the summer solstice and the fall equinox. Before I moved back to D.C., I doubt I knew what a cross-quarter day was.

The triumph of Christianity over paganism, considered a civilizational advance by the winners (surprise surprise), had also marked the “triumph” of a solitary male god over a pantheon that included goddesses as well as gods. As it turned out, over the centuries and millennia the goddesses in those pantheons had been losing power and status to the gods. In the myths I learned growing up, Hera had power but Zeus had more. It had not always been so.

I came to see Mary in a new light, as a vestige of the once powerful goddesses. The relentless male supremacists of the early Christian Church hadn’t been able to stamp her out. They co-opted her instead. Paradoxically enough, the intensely sexist and often misogynist Catholicism I’d encountered at Georgetown had a female side that the Episcopalianism I’d grown up with lacked.

The Christians were adept at co-opting what they couldn’t entirely suppress. Many major Christian holidays piggy-backed (that’s a polite term for it) on the old pagan solstices, equinoxes, and cross-quarter days: Christmas is Yule (winter solstice), Easter (spring equinox), and so on. The pagan year began with Samhain, Halloween, which I like most of my cohort learned about as a kid in single digits.[2] Clearly there was much more to it than trick-or-treating.

Lammas celebrated its anniversary every year with champagne and a big sale; the ceiling of the Seventh Street store was cork-pocked from those celebrations. Lesbian households might observe the various pagan/wiccan holidays, and often enough there were well-attended public rituals that featured singing, poetry, and lots of candles. We identified ourselves to each other by the jewelry we wore (pentacles, labryses,[3] goddess figures), the greetings we exchanged, and of course our T-shirts.

Pulling off my shelves the books that I devoured then and haven’t let go of, I can’t help noticing how many were published in 1979, just as my curiosity was flowering:

- Starhawk’s The Spiral Dance, which introduced me and countless others to the Wheel of the Year and wiccan rituals

- Margot Adler’s Drawing Down the Moon, a journalist’s in-depth survey of, as the subtitle put it, “Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today” (an expanded edition was released in 1984)[4]

- Merlin Stone’s two-volume Ancient Mirrors of Womanhood: Our Goddess and Heroine Heritage, a compilation of goddess stories from every continent inhabited by humans

- Part 1 of Z. Budapest’s The Holy Book of Women’s Mysteries (part 2 came out in 1980)

- Elaine Pagels’s The Gnostic Gospels, which explored the early texts that didn’t make it into the Christian canon, in which God was seen as both Mother and Father

- JEB’s Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians, which includes several witchy photos and witchy quotes

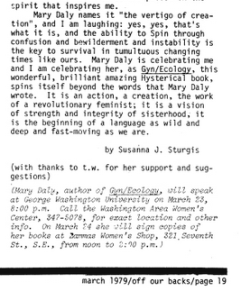

The previous year’s crop is just as impressive. Among the feminist essentials with major pagan connections published in 1978 were Mary Daly’s Gyn/Ecology, Sally Gearhart’s The Wanderground: Stories of the Hill Women, Susan Griffin’s Woman and Nature: The Roaring Inside Her, and the paperback of Merlin Stone’s When God Was a Woman.

Considering the time it takes to produce a book-length work, from research and writing through to physically producing it and getting it into the hands of interested readers, it was obvious the cauldron had been bubbling for quite some time.

For women awakening to feminism in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the past looked like a wasteland. But once women got to work researching and revisiting, rethinking and rearranging, the desert bloomed. For us coming of age in the 1960s, ’70s, and into the ’80s, as women’s studies professor Bonnie Morris writes, “It became second nature to have to look hard for lost history.” She compares it to “the upbeat excitement of a fierce girl detective searching for clues.”[5]

Among many other things, we learned that men called women “witches” in order to persecute, prosecute, and not infrequently kill them, and that this often had little or nothing to do with religion. Women who used herbs, touch, and common sense to heal were said to be practicing magic — exercising powers that men didn’t have and didn’t understand. As the male-dominated medical profession rose in influence, female healers were marginalized, their wisdom dismissed as superstition and “old wives’ tales.”[6]

The history that could be documented or otherwise proven beyond reasonable doubt was crucial, but so were the improvisations, the mythmaking and rituals, inspired by it. Some of the most-quoted lines of grassroots feminism came from Monique Wittig’s Les Guérillères, published in 1969 and translated into English in 1971. They describe pretty well what we were up to: “There was a time when you were not a slave, remember that. You walked alone, full of laughter, you bathed bare-bellied. You say you have lost all recollection of it, remember . . . You say there are no words to describe this time, you say it does not exist. But remember. Make an effort to remember. Or, failing that, invent.”

Remember. Make an effort to remember. Or, failing that, invent.

Monique Wittig, Les Guérillères

NOTES

[1] A Google search just turned up this short Washington Post piece about the course from 1993. It confirms my memory that Father Sebes’s background was indeed in Far Eastern studies; while living in China from 1940 to 1947, he spent part of the time interned by the Japanese. It disputes my description of him as “older”: born in 1915, he was only a few years older than my parents, who were both born in 1922. The author writes that “Comp Civ” was popularly known as “Buddhism for Baptists,” but I never heard it called that — and why Baptists? I couldn’t have told you which of my non-Catholic classmates came from Baptist households. Protestant denominations were all lumped together as “Other.”

[2] Halloween was also my mother’s birthday. I could tell a few stories about that, but instead I’ll tell one that my mother repeated fairly often. Her father (an embittered, said-to-be-brilliant upper-crusty WASP man) would tell her “You were born on Halloween so you’re a witch. If you’d been born a day later, you would have been a saint.” Nov. 1 being All Saints Day in many Christian calendars. Witches to me were Halloween, the Salem witch trials, and The Wizard of Oz. Glinda to the contrary, my associations weren’t positive.

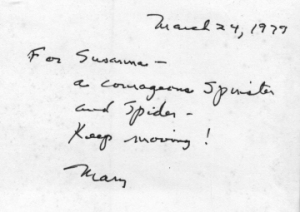

[3] The labrys, a double-headed axe, originated in ancient Crete and has been adopted especially by lesbian feminists as a symbol of female strength. It was all over the place in the 1970s and beyond, on T-shirts and pottery, in jewelry and artwork. There are two classic examples in my Mary Daly blog post, one on a T-shirt and one in Mary’s hands. Mary was a hardcore labrys fan.

[4] One of life’s little synchronicities: Margot Adler and her longtime partner, John Gliedman, had their handfasting at the Lambert’s Cove Inn in West Tisbury when I was a chambermaid there: June 18, 1988, I’m told by this very good biographical article about her. The inn hosted many weddings during the years I worked there (1988 to 1990 or maybe 1991), but this was by far the best. I was just reminded that Adler’s middle name was Susanna, spelled the way I spell it.

[5] In The Disappearing L: Erasure of Lesbian Spaces and Culture (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2016). I hope The T-Shirt Chronicles will do its bit to push back against this erasure.

[6] In one of the many, many instances of reclaiming that have characterized feminism, “Old Wives Tales” was the name of San Francisco’s feminist bookstore. An excellent source on the how patriarchal medicine stigmatized women healers is Adrienne Rich’s Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution. First published in 1976, it’s still in print.

If you want to leave a comment and don’t see a Leave a Reply box, click the title of the blog post (above) and then scroll to the bottom.