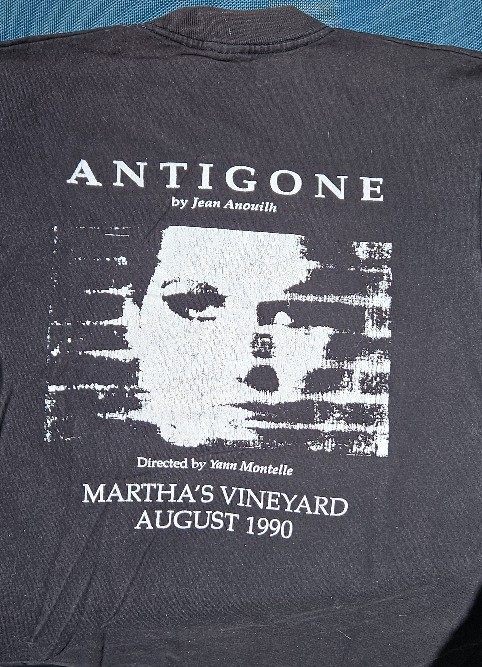

The second of my two show-specific shirts, unlike the first, commemorates a production mounted entirely on the Vineyard, but not by either of the two established theater companies, Island Theatre Workshop and the Vineyard Playhouse.[1]

Seen from several decades later, the late 1980s and early ’90s were a golden age in Vineyard theater, and in the grassroots performing arts in general. “The Play’s the Thing,” a July 1990 story in the Martha’s Vineyard Times summer supplement, counted no fewer than seven companies in action that summer.[2]

Essential to this flowering was available space.[3] The Vineyard Playhouse could host full productions upstairs, and smaller ones downstairs, like the late-night comedy troupe Afterwords. Island Theatre Workshop (ITW) didn’t have its own home, but it had regular access to Katharine Cornell Theatre, upstairs from Tisbury Town Hall, and, for auditions and early rehearsals, to the parish hall at Grace Episcopal Church not far away.

Once Wintertide moved into its year-round home at Five Corners in January 1991, all sorts of creativity took root and flowered there, including WIMP, the Wintertide Improv group. Among WIMP’s offerings was “Troubled Shores,” a long-running soap-opera-style satire of island life.[4] I still vividly remember Theodore Sturgeon, chief surgeon at Wing and a Prayer Hospital (Toby Wilson), Sengekontacket Vanderhoop (Lisa Elliott), and John Farmboy (Chris Brophy).

Some performers and techies were identified primarily with one or the other theater groups, ITW or the Vineyard Playhouse, but most moved between them and Wintertide depending on available opportunities. Having both space and a pool of capable actors and tech crew available made it so much easier to mount a show than it would have been if you had to start from scratch.

Not only to mount a show, but to birth a new theater company: Chiaroscuro, the company behind the 1990 production of Jean Anouilh’s Antigone, was born on Martha’s Vineyard. Ironically, when Yann Montelle arrived on the Vineyard to visit a friend on Chappy, he was taking a break from theater in his native France. Then fate intervened: he met, then married, Anne Cook, an artist with a long family connection to the Vineyard. Together they founded Chiaroscuro.

Yann and Chiaroscuro were active on the Vineyard for well under two years before Yann and Anne left for Portland, Maine, but the energy and quality of their activities were astonishing and invigorating to the island’s theater scene. In addition to directing, Yann ran workshops, at least two of which grew into full productions: Macchiavelli’s The Mandrake and Molière’s The Misanthrope. Of the former, he later told an interviewer[5] that “I wanted to do it to see if I could speak English. I had trouble because – you guys don’t realize it but you speak very fast!” To say he quickly became fluent is an understatement.

Yann also collaborated with fellow Frenchman Dominique Pochat (1956–2003) in the latter’s Red Nose Reviews, featuring Martin, Dominique’s clown persona. Dozens of Vineyarders, actors and non-actors, took their workshops; Red Noses started appearing in unexpected places. Red noses, by the way, have long been associated with clowns, but where did they come from? Origin stories vary: poke around online and you’ll find some of them. They’ve been described as “the smallest mask in the world.” I love this. With a red nose on, your face becomes both yours and not-yours. You’re free to become a you that isn’t seen in polite company.

And Yann directed several outstanding shows in 1990 and 1991. In addition to Antigone, I remember especially The Merchant of Venice (summer 1991) — which like Antigone was staged at the outdoor Tisbury Amphitheater[6] — and Sartre’s No Exit. I have copies of the reviews I wrote of several of these shows, so it’s not hard to remember the details. About Antigone I wrote that it was “one to see more than once, to discuss passionately far into the night over cappuccino or wine. Directed with care, graced with several outstanding performances, this ‘Antigone’ jerks you back and forth by the hair and leaves you breathless, dizzy, even awed.”

Randy Rapstine, who appeared in both Antigone and Merchant as well as other Vineyard productions (and with the Afterwords troupe), was one of several theater people who were then moving regularly between New York and the Vineyard. Asked to compare the two scenes, he noted that “in New York, you’re a small fish in a big pond,” while the Vineyard provided opportunities that were rare in New York. As a result, actors can take on a range of roles so audiences “see different parts of you.” He praised Vineyard theatergoers for being willing and able to do that.[7]

NOTES

[1] They rarely if ever created a T-shirt for a particular show. This makes sense. From auditions through rehearsals to opening and then closing night, a production’s life cycle might be eight weeks at most. Designing a shirt from scratch, then getting it printed and out on the street, would probably take at least four, by which point the run would be half over.

[2] For the record, they were the Vineyard Playhouse Company, Chiaroscuro Theatre Company, Full Circle, Island Entertainment Productions, Island Theatre Workshop, Red Nose and More, and Theater Arts Productions. The story was by yours truly.

[3] Also important was reasonably affordable housing. Year-round housing could usually be found at a realistic (for the Vineyard) price, and seasonal actors and techies could be put up in the spare rooms of year-rounders. As time went on, spare rooms became scarce, in part because young people who’d grown up on the Vineyard couldn’t afford to move out on their own.

[4] Led by WIMP veteran Donna Swift, Troubled Shores became the name of a Vineyard nonprofit focusing on theater (including improv) for young people on the Vineyard.

[5] That would be me. This was sort of Yann’s exit interview from the Vineyard: “Yann Montelle Seeks Out New Risks,” Martha’s Vineyard Times (August 29, 1991).

[6] If in warm weather, especially toward the end of the afternoon, you see vehicles parked bumper to bumper on both sides of State Road near the Tashmoo Overlook, that’s a sure sign there’s a show on at the Tisbury Amphitheater. This is a glorious clearing in the woods with a natural embankment that’s been augmented with very basic seating, e.g., railroad ties. Playgoers often bring their own beach chairs or blankets, and often a picnic. If you’ve never been there, pull off on the overlook when there isn’t a play going on, start walking down the access road, then take one of the paths on your right that leads into the amphitheater itself.

[7] Writing in the T-Shirt Chronicles about people I knew decades ago, I’m often afraid to look them up online. Randy was so talented and so motivated but the New York theater scene is so crowded and demanding. I didn’t want to learn that Randy had given it up and become a stockbroker. Good news: His subsequent career has included directing, producing, and teaching as well as acting in films as well as theater, and he’s still at it. Check out his website for details.