I’d been writing for publication for several years before I decided that I needed something more. I was well enough educated, but as a writer I was largely self-taught. I belonged to Hallowmas Women Writers, a group of D.C. poets and writers that I’d helped form. It was a lifeline to my writer self, its members were doing interesting work, but all of us were engaged in other activities and I was discontented with the feedback I was giving as well as getting. As a fledgling editor, I’d benefited tremendously from working alongside someone who knew a lot more than I did and was willing to share. Were there comparable opportunities out there for women writers?

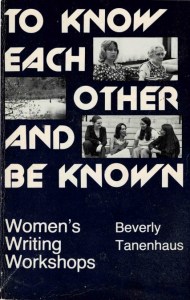

off our backs carried ads for the Feminist Women’s Writing Workshops (FW3), a 10-day live-in workshop held every summer in upstate New York. Founder-director Beverly Tanenhaus’s book about the workshops, To Know Each Other and Be Known (Motheroot Publications), came out in 1982. Lammas must have carried it, I must have noticed it, but I don’t think I’d actually read it. My copy has “July 1986” written under my name on the title page, which suggests I acquired it at the workshop that year.

I sent for the workshop brochure on February 5, 1984. Tuition, room, and board was $475, $425 if you applied by March 15. Could I afford it? Could I get 10 days off from Lammas in the middle of July? Where the hell was Ithaca, and how would I get there? I didn’t own a car, and my grasp of upstate New York geography was hazy.

Scariest of all, was I really ready? I didn’t know anyone who’d attended the workshop and could assure me that I wouldn’t be in over my head. The biggest risks I’d taken, like moving back to D.C., applying for that editorial job at the Red Cross, and becoming the book buyer at Lammas, had all turned out well. What if this one didn’t?

I sent in my deposit in time to get the early bird discount. My welcome letter from the director was dated March 16. The stars aligned, the logistics worked out, and I arrived by bus in Ithaca on July 15.

To say that the workshop was life-changing is both a cliché and an understatement. Our introductory session that first night opened with a recording from the first FW3 in 1975, of Adrienne Rich’s prose poem “Women and Honor: Some Notes on Lying.” This was already, and has been ever since, the closest thing I have to a bible. It’s about the importance of telling the truth to each other (and, by extension, to ourselves). What better way to challenge us as writers?

Our morning class sessions were held in the second floor of the Wells College boathouse, with Cayuga Lake glittering out the window and lapping gently at the shoreline. Each morning, an hour was devoted to the work of each of two participants. Copies had been distributed the previous day, and all of us came prepared. The guidelines: Comments were to be directed to the director, or to each other — not to the writer. The writer’s job was to listen until everyone had spoken, then respond at the end of the discussion. The power of 18 women focusing entirely on my work, taking it seriously for a solid, animated hour, was a revelation. So was the challenge of being one of the 18 women giving feedback to another writer, overriding the voices in my head whispering things like What if I’m wrong? What if I’m missing something? What if this isn’t all that important?

The rest of the day was open. Most of us gathered for meals in the cafeteria — the luxury of not having to prepare our own meals wasn’t lost on any of us — but the rest of the time we went our own occasionally intersecting ways in ones, twos, and threes, walking in the woods, swimming in the lake, writing in our rooms, sitting under a tree or by the lake to write or read.

During the week groups of us took field trips to the National Women’s Rights Historical Park at Seneca Falls, which had opened only two years before, and the National Women’s Hall of Fame, or into Ithaca, to hang out at Smedley’s, the feminist bookstore (proprietor Irene Zahava had been a workshop participant in the past and has edited many, many anthologies of women’s writing over the years), and of course to eat at least once at Moosewood Restaurant.

Poet-novelist Marge Piercy was the guest writer that year, in residence for a couple of days. We also heard from Elaine Gill, co-principal of Crossing Press, then located in nearby Trumansburg, and Nancy Bereano, who had edited Crossing’s Feminist Series and was just then establishing her own Firebrand Books, which quickly became a major player in the feminist print world.

As the re-entry meeting began on the last night of the workshop, I was feeling sad and euphoric, hopeful and apprehensive all at once. We had created magic; would I ever see these women again? As a writer I felt validated and capable; could I maintain my momentum when I got back to D.C.? We went round the circle, each woman sharing what she was going back to and what she was taking home with her. All of us had taken to heart the words of Adrienne Rich at our very first meeting: “When a woman tells the truth she is creating the possibility for more truth around her.”

Almost all of us, as it turned out. About two-thirds of the way around the circle, the workshop blew up. There were four lesbians at the workshop that year, of whom I was one. At the re-entry meeting, the other three charged the rest of us with making them feel unwelcome. They didn’t target me specifically — they didn’t target anyone, and were rather short on specific examples — but I was undeniably on the wrong side of a lesbian-straight split.

After the instigators left the room, most of the rest of us came together to talk about what had happened. We shared our immediate reactions. Most of us tried to identify what we had done to make the three women feel unwelcome. As the only lesbian in the circle at that point, I said I hadn’t felt unwelcome at all. I was a little surprised by this, because I was no stranger to the tensions that sometimes arose between lesbians and straight women in feminist spaces.

The D.C. lesbian feminist community and the national Women in Print network had become my home in a way that my growing-up home wasn’t. They were where and how and why I became a writer: developing my skills, giving me no end of things to observe and think and write about, seeing my words in print, and providing an audience (which I was also part of). So though I did spend time with the other lesbians at the workshop, hanging out with them wasn’t a priority. Connecting with sister writers was. Being taken seriously as a writer was.

Our shared effort that night to come to grips with what had just happened, speaking first-person and from the heart, was rare in my experience — so rare that in the months that followed I wrote a 6,000-word essay (never published) about the workshop experience. I still have the copy I shared with another workshop participant, with her extensive and thoughtful comments on it: she agreed with some of my points, challenged others (sometimes strenuously), and expanded my perceptions of what had happened.

I was willing then, and I’m willing now, to believe that the other three lesbians had experienced lesbophobia at the workshop, even though I had not. My problem then and now was with how they chose to bring it up, starting with the timing. The second-to-last night of the workshop had been devoted to a “creative bitching” session. We talked about what worked at the workshop and what could be improved in the future. Rather than bring their issues up then, the three chose to bring up their complaints at the re-entry session, our last time together as a group. Everyone would be leaving the next day. The three timed their confrontation so they wouldn’t have to deal with its consequences, or even see any of us face-to-face again. Then they walked away from the possibility of expanding truth to include all of us.

In an article about FW3 1986 for Hot Wire, the women’s music and culture journal, I wrote: “Perhaps the hardest lesson to learn is that inclusion in community here depends largely on a willingness to risk telling and hearing the truth — a willingness that is, not coincidentally, essential for feminist writing” (Hot Wire, March 1987).

I learned later that the main instigator of the confrontation had lobbied for a position as an assistant workshop director for the following year and been turned down. Was revenge at least part of her motive? I suspect so. As it turned out, the director asked me to be one of her assistants the next year, which enabled me to attend the workshop free of charge. Of course I accepted, and continued as an assistant through 1987. By the summer of 1988 I’d been hired as proofreader at the Martha’s Vineyard Times so taking 10 days off in the middle of July was out of the question.

Before I left for my annual end-of-summer visit to the Vineyard in 1984, my first workshop year, a crafty (in more ways than one) member of Hallowmas Women Writers gave me an amulet bag she’d crocheted for me. For a while I wore that amulet bag around my neck with nothing in it. Then while I was walking on South Beach one afternoon an oblong bit of white-and-purple clam shell caught my eye. Into the amulet bag it went. When I returned to D.C., I wore it everywhere.

For a long time I liked to attribute my decision to move to Martha’s Vineyard to that amulet. There was, need I say, more to it. For years the lesbian feminist community and my writing had fed each other, confirmed each other, formed a dynamic whole. In the early ’80s fissures were growing just below the surface. In the early to mid 1980s AIDS, a barely identified syndrome with a dismal prognosis, was devastating the gay male community. Meanwhile, the lesbian community was polarizing around the so-called sex wars. The front lines included pornography and s/m, which one side saw as irredeemably misogynist and the other as liberating. Women I knew and admired were on both sides; the accusations were ugly and loud. As a writer I felt caught in a middle that was critical of both factions and wasn’t being heard. Did that middle even exist?

My experience at the 1984 Feminist Women’s Writing Workshop helped clarify and focus my uneasiness. If the community of lesbians and the community of writers diverged, my path would lie with the writers.

Looking back later, I realized that my urge to “get out of Dodge” had plenty to do with the Reagan administration, which altered the feel of D.C. whether you had any connection to the federal government or not. In July 1985, I left D.C. with all my belongings in a rental truck, deposited them in the basement of my parents’ home in the Boston suburbs, returned to the Feminist Women’s Writing Workshops for my first year as an assistant director, and by the end of the month was more or less living on Martha’s Vineyard.