I acquired my SECEDE NOW T-shirt on Martha’s Vineyard in the late 1970s, years before I moved to the Vineyard year-round, though I was spending time there now and then. It’s now so historic that mine was recently included in a T-shirt exhibit at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum. Here’s the story behind it: In 1977, the Massachusetts House of Representatives reduced its number from 240 to 160. Among the districts eliminated in the reduction were Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, which up to that time had each had its own seat in the House. This provoked indignant threats to secede from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and generated, along with this T-shirt, a striking flag that is still occasionally seen in these parts.

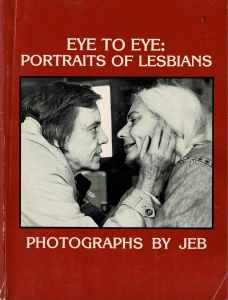

My SECEDE NOW story has nothing to do with the Massachusetts legislature, or Massachusetts either: it unfolded in D.C., around 1980. If I had to identify the five most important turning points in my adult life, this would be one of them. It’s about daring to be seen, and it starts with the 1979 publication of JEB’s Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians.

Eye to Eye was a revelation, an inspiration, a major milestone on the road to lesbian visibility. The local impact might have been even greater than the national one: JEB (Joan E. Biren) had long been a visible mainstay of the D.C. lesbian community — she was a veteran of the Furies collective — and many of the women depicted in its pages lived in and around D.C. I had at least a nodding acquaintance with several of them, and would get to know some much better in coming years. Of course I bought Eye to Eye as soon as it came out, and you bet I’ve still got my copy.[1]

Every woman who appeared in Eye to Eye was unfathomably brave. As a writer in the Unicorn Times, a D.C. alternative newspaper, put it when the book was released: “It is almost impossible to publish photos of lesbian mothers with their children because of the mother’s fears of losing their children in custody cases. Mothers are not the only lesbians who can’t be photographed. Women afraid of losing their jobs, lesbians from other countries afraid of deportment, and lesbians afraid of disownment from their families all had to refuse Biren’s permission to be published.”

Those sentences were quoted in Paul Moakley’s excellent (I’m serious about this. Read it!) interview with JEB for Time magazine in February 2021, when Eye to Eye was reissued in hardcover, the original intact but expanded with new essays. In 2021 it may be as pathbreaking, as revelatory, as it was in 1979. Lesbians are on TV these days, we can get married, and so on, but we’re submerged in the LGBTQ coalition (in which G has been dominant from the beginning) and erased by supposedly inclusive words like queer and gender-nonconforming. We’re invisible in a whole new way.

In 1979 I did notice an absence in Eye to Eye, however: women who were fat like me. The absence wasn’t total: Dot the chef is what I’d call zaftig, but she was also middle-aged, which to my 28-year-old mind let her off the looks hook; and one of the quintet gathered around the National Lesbian Feminist Organization banner at the 1978 ERA march might have been around my size. But none of the women photographed bare-breasted or naked were anywhere close to zaftig, never mind fat.

I got it, or thought I did: a powerful stereotype at the time (which hasn’t entirely gone away) was that lesbians turned to women because they “couldn’t get a man,” and being fat got you sorted PDQ into that category. I took for granted that being fat made you a liability, that Eye to Eye would be taken more seriously if we weren’t in it. I felt petty for even noticing our absence. Of course I didn’t mention it when I reviewed the book. I doubt I ever even said it out loud.

Then Beth K., a D.C. photographer whom I knew from my Washington Area Women’s Center days, announced that she was planning a show of lesbian portraits. Each image would be accompanied by the woman’s own words. Rather than choose her subjects, she was soliciting volunteers from the community. Words coupled with images! I was a writer, after all — wasn’t this right up my alley? My written words went out in public all the time. Writing short was a challenge (still is), but I could do it.

But–but–but . . . Being a fledgling editor as well as a writer, I could control my words; often I even had some say about how they appeared in print. I would have zero control over how I appeared in a photograph, or of what people would see when they looked at it. If people could see what I looked like, would they still take my words seriously?

My ruthlessly rational feminist self went up against against my own muddled assumptions. Fat lesbians were a liability — did I believe I was a liability? (Yes.) Did I see the connection between believing my physical appearance made me a liability and railing against a misogynist culture that valued women according to their physical appearance? (Uh . . . yeah. Sort of.) What was this really about? (I’m terrified.) Of what? (Seeing what I really look like.) So if Beth asks if you’d like to be in the show, what are you going to tell her?

And that’s where I choked. My “reasons” flourished in the privacy of my head,[2] but if I said them out loud to someone else, even I would have to see what crap they were. By asking for volunteers, Beth had given me the opportunity to say yes. If I didn’t say yes, I better shut up about the absence of fat lesbians from books and photo shows. So I said yes.

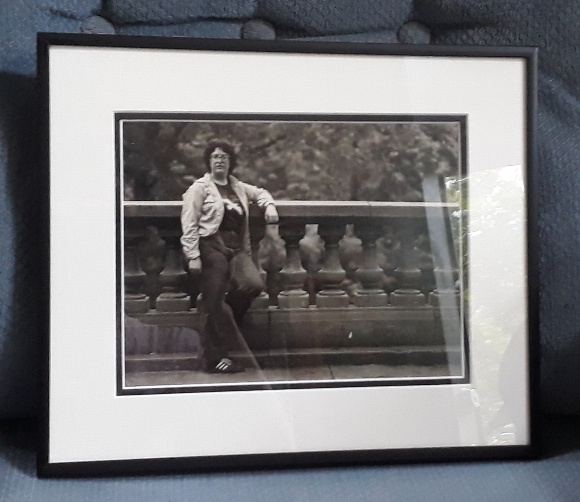

Here’s the photo, which I just had reframed. I chose the location: a stone bridge over Rock Creek behind the National Zoo, not far from where I lived, which I biked over several times a week going to and from work in Alexandria. I wore my SECEDE NOW T-shirt as a personal declaration of independence.

I don’t have a copy of what I wrote for the show; I might have lost it, or it might be buried in one of the file drawers I have from before “files” were saved on disks or hard drives or in the cloud. I remember comparing being a lesbian to being a writer: nature and nurture — potential — had something to do with both, but decisive in both cases were the choices I kept making over time. The choice to say YES to being photographed was a big one.

What I see when I look at that photo today is a young woman who, despite being uncomfortable in her own body and uneasy about being seen, is standing out in the open. She hasn’t partially concealed herself behind a tree, or at a typewriter. She’s meeting photographer and camera eye to eye.

Forty-plus years later I meet her likewise and salute her courage.

If you want to leave a comment and don’t see a Leave a Reply box, click the title of the post and then scroll to the bottom.

notes

[1] I’m not the only one. In the Time interview cited above, JEB says: “For years I would go into my local gay bookstore to their secondhand section. It was never there. Never! Today people are all telling me they still have the one they bought in 1979. . . . I gave a copy to my college library (Mt. Holyoke), and it was stolen—maybe like seven times. Eventually, they had to lock it up in the stacks, where they had this cage with all the rare books from the Middle Ages.”

[2] Pete Morton hadn’t written “Another Train” yet, but he nailed it (and a few other things) in that great song: “Imagination plays the worst tricks.” When I first heard “Another Train” — covered by the Poozies in the mid-1990s — I was sure Sally Barker was singing to me, her invisible arm around my shoulders in some bar somewhere. That led me to Pete Morton’s own version, and a whole slew of his CDs. I’m still hoping to hear him live some day . . .